Blocking long-planned oil and gas projects would risk leaving UK consumers even more exposed to the global energy shortages that sent bills soaring this winter, industry experts have warned.

OGUK, the trade body which represents the UK’s offshore oil and gas industry, says the projects planned by its members are essential to maintain production and protect UK consumers during the planned transition to lower carbon forms of energy.

The warning follows the debate over the Cambo oil and gas field, planned 75 miles west of Shetland. It would deliver 170 million barrels of oil, plus some gas, over 20 years. This week Nicola Sturgeon joined environmental groups in suggesting such projects should not go ahead, citing concerns over climate change. The final decision rests with the UK government which has long recognised the need for secure energy supplies.

OGUK’s research shows, however, that the UK is already becoming highly reliant on other countries and has to import half its gas. The UK government’s latest trade figures show that, in the year to June, the UK paid:

– Norway £5.2 billion for gas plus £6.1 billion for crude oil

– Russia £524 million for gas and £3.2 billion for oil

– Qatar £675m for liquefied natural gas

– USA £2.8 billion for crude oil.

OGUK is warning that if new projects like Cambo are not approved then UK production would plummet with gas output, for example, falling up to 75% by 2030. This would leave the UK increasingly reliant on imported energy.

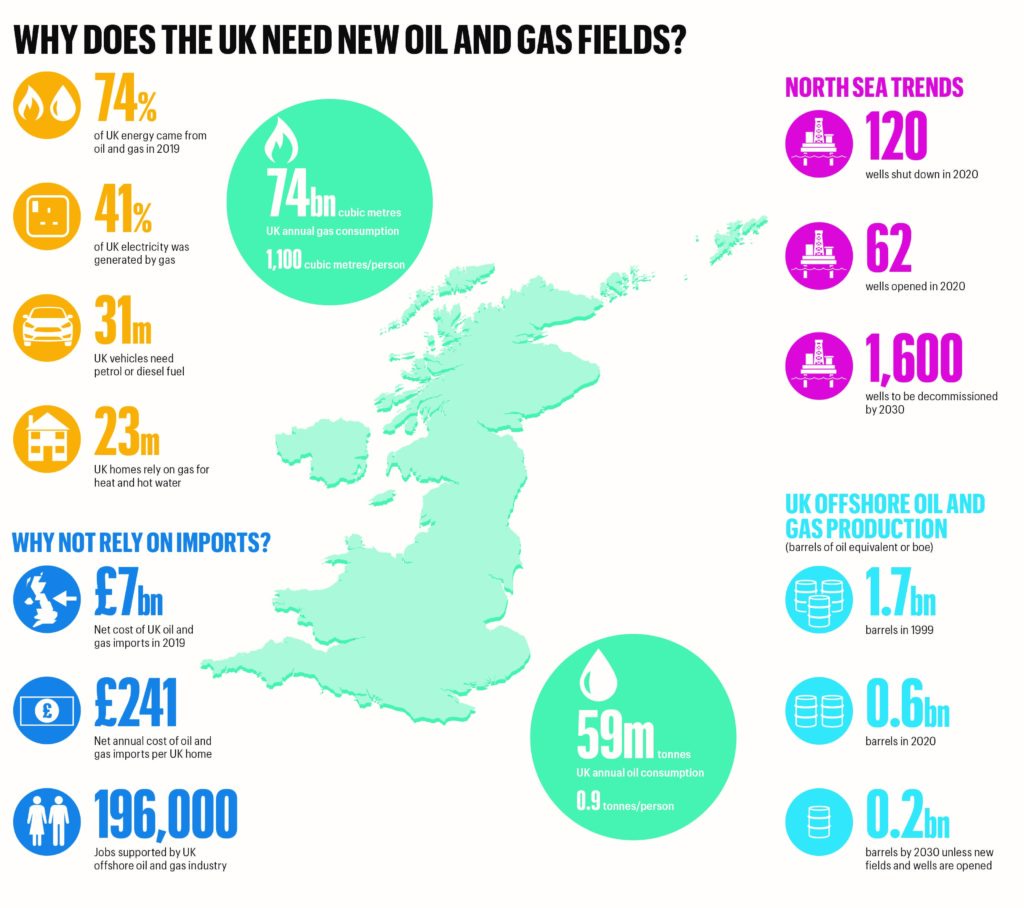

The UK economy relies on oil and gas which together provide 73% of the nation’s total energy (78% in Scotland). About 24 million homes are heated only by gas which also provides 41% of our electricity. The UK has 32 million private cars and other vehicles that need diesel or petrol. The government has plans to reduce this demand, but they will take years to implement, during which the UK will continue to need oil and gas, more than 15 billion barrels over the next 30 years.

Cambo is one of a number of discoveries which could help meet those needs and which are now only awaiting approval by regulators and formal sign-off by the government. All have been years in the planning, overseen by the government’s regulators, the Oil and Gas Authority. These projects will be among the world’s cleanest oil and gas projects. The industry is driving down emissions from the production of oil and gas in UK waters, as set out in the North Sea Transition Deal, aiming to reach net zero by 2050.

The emissions generated by consuming the oil and gas extracted from such projects have also been included in the Climate Change Committee’s carbon budgets. These government-approved plans include continuing but declining use of oil and gas for at least the next three decades.

Why, though, does the UK need new oil and gas projects? In some regions, such as Russia or Qatar, oil and gas fields can be huge and remain in production for decades. The geology of the North Sea is different – our industry is based largely on hundreds of small and medium sized wells and fields spread across the UK Continental Shelf. This mean there is a high rate of churn where older fields become too difficult and expensive, so the wells and installations within them are made safe and decommissioned This is already happening and is why new projects like Cambo are needed – to replace declining production.

What’s important for emissions is the overall amounts of hydrocarbons produced – which are falling. UK oil and gas production peaked in 1999 when our continental shelf produced the equivalent of 1.7 billion barrels of oil equivalent (boe). By 2020 this had fallen to 587 million boe. This downwards trend will continue, even if some new projects are opened, because the UK continental shelf has been operating for five decades and is in natural decline.

Deirdre Michie, chief executive of OGUK, said:

“The UK’s offshore oil and gas industry is committed to helping the UK government meet its ambitious net zero goals. We accept all the science around climate change and the need to cut emissions, but this transition must be managed.

“If we cut our own supplies of gas and oil faster than we can reduce demand then we will have to import more of what we need. Our import bills will go up without any reduction in emissions.

“That means we need to develop new oil and gas reserves simply to maintain domestic production

“These new projects will help protect consumers, supply the UK with lower carbon energy, reduce our need for imports and support the 200,000 people working in the industry as it transitions to a greener low-carbon future.”

ENDS

BACKGROUND BRIEFING BY OGUK

Why does the UK need new oil and gas fields?

Proposals to develop new oil and gas fields on the UK continental shelf, such as the Cambo field 125km west of Shetland, have attracted widespread interest. This briefing aims to put these plans into a wider context, showing that, these fields are part of a continuous process that sees some oil and gas fields being opened or expanded every year – while older ones close

This ‘churn’ is due to the geology of the UK Continental Shelf (UKCS). It has hundreds of oil and gas reservoirs, but most are small relative to those in major oil and gas producing countries like Russia and Saudi Arabia. This means there are always some fields approaching depletion and decommissioning.

It also means UK operators need to open new fields, or expand existing ones with new wells, simply to maintain output and keep meeting demand. Newer fields will generally have much lower carbon footprints than older ones because installations are being designed to maximise energy efficiency, minimise leakage of gas, avoid routine flaring or venting and made ready to run on low-carbon electricity rather than use gas to generate their own power.

In 2020, for example, drilling commenced on more than 65 new wells across the UKCS – while 116 older wells were decommissioned. New fields like Cambo are part of that steady turnover.

What’s important for emissions is the overall amounts of hydrocarbons produced – which have been falling for some years. UK oil and gas production peaked in 1999 when our continental shelf produced the equivalent of 1.7 billion barrels of oil equivalent (boe). By 2020 this had fallen to 587 million boe.

This downwards trend will continue, because the UK continental shelf has been operating for five decades and is in natural decline. The UK has some control over how fast that decline happens by continuing to drill new wells to increase recovery in existing fields or by opening new fields. If there were no such new projects, then oil and gas production is predicted to decline by 75% by 2030 – meaning UK imports would rise, impacting our balance of payments and destroying skilled jobs. If the UK did approve the projects for which applications are in the pipeline the long-term decline would continue but it would be slower and more orderly – and offer better energy security for consumers.

Production emissions are also falling. These are the emissions generated by extracting and processing oil and gas and equated to 17 million tonnes of CO2 in 2020. The industry has committed to reduce these to net zero by 2050.

So, the debate over opening these new resources should be seen as part of a much wider debate over how much oil and gas the UK will need over the next three decades and where we should get it from. The question for policymakers is how quickly we want that production to decline, given the country’s continuing demands for oil and gas.

How reliant is the UK on oil and gas?

OGUK’s Economic Report (September 2021) showed that oil and gas provided 73% of the UK’s total energy in 2020 so these fuels are still central to our lifestyles and our economy. For Scotland the levels are even higher – in 2020 it relied on oil and gas for 78% of its total energy and 91% of its heating. OGUK’s report also found that, between now and 2050, up to half the UK’s energy will still need to come from oil and gas.

Consumption should decline as the energy transition progresses but production is also in a parallel natural decline so the UK will continue to need more oil and gas than it produces. That means imports will always be needed. Cambo and other proposed new projects would reduce the amounts of those imports.

GAS FACTS: (from DUKES)

- In 2020 the UK consumed 74 billion cubic metres of gas.

- This works out at 1,100 cubic metres of gas for each of the UK’s 65m citizens.

- About 23 million homes rely on gas for heating. There are 28m UK households so 83% depend on gas.

- The UK has 35 gas fired power stations providing about 41% of our electricity.

- About half the gas consumed in the UK came from UK sources – the rest was imported

Where does our gas come from?

The UK Continental Shelf (UKCS) supplied all the UK’s gas needs till 2004 but the proportion has dwindled as older gas fields are depleted. It will keep shrinking unless new reserves are opened to replace them. Without new reserves production will fall 75% by 2030, compared with current levels. That would leave the UK increasingly reliant on imports and on volatile global markets – potentially risky in a world where demand for gas is surging.

Imports already supply about half the UK’s gas. In 2020 about 27 billion cubic metres of gas were imported from Norway by pipeline. Another 18 billion cubic metres were imported as liquefied natural gas of which 9 billion came from Qatar and 3 billion from each of America and Russia. Russia is also a major pipeline gas supplier to continental Europe, and there are pipelines linking the UK to Europe.

OIL FACTS: (from DUKES)

- In 2019 the UK consumed 59 million tonnes of oil and oil products such as petrol, diesel and aviation fuel

- This amounts to just under a tonne of oil per UK citizen.

- Transport is the primary use. About 32 million cars, vans and lorries rely on petrol or diesel

- The UKCS produced 53 million tonnes of oil

- About 45 million tonnes of UK-produced oil were exported for refining

- The Netherlands and China were the biggest purchasers of UK crude oil

- The UK imported 51 million tonnes of oil and oil products

Where does our oil come from?

This is more complicated than for gas because oil must be processed into products like petrol, diesel, and aviation fuel before it can be used. The UK produces mainly ‘premium crudes’, meaning they are relatively simple to refine and so in high demand. Much of it is exported to refineries in global hubs such as the Netherlands.

Each refinery tends to specialise in different grades of crude oil and in producing particular fuels and chemicals. The UK then imports the fuels and other refined products that it needs to balance customer demand with domestic refinery production.

What is the UK Continental Shelf?

The UKCS is the region of water around the UK over which the nation has mineral rights. It includes parts of the North Sea, North Atlantic, Irish Sea and Irish Channel. The UKCS is bordered by Norway, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, France, and the Republic of Ireland. A median line, setting out the domains of each of these nations was established by mutual agreement and this is set out in the Continental Shelf Act of 1964.

UKCS Statistics

261 – Total number of active (manned) installations extracting oil and/or gas

234 – Number of installations producing crude oil

186 – Number of installations producing natural gas

182 – Number of installations producing both gas and oil

27 – Total number of companies operating installations in the UKCS

What is Cambo?

The Cambo field lies 75 miles west of Shetland, under 1,100 metres (3,600 feet) of water. Based on exploratory wells and other data, Siccar Point Energy (which has a 70% share in the project) and Shell (30%) believe Cambo could produce 170 million barrels of oil (25 million tonnes), plus 1.5 billion cubic metres of gas, over the next two decades.

NOTE: Cambo is often described as containing 800 million barrels of oil. This is an estimate of the total contents, but the amount extracted will be far less – about 170 million barrels.

For context, the UK uses about 1.5 million barrels of oil a day.

How will Cambo work?

The proposals involve drilling multiple wells, four of which will be used to inject water into the underlying rock to force the oil and gas out. It would emerge via nine production wells and be pumped into a Floating Production, Storage and Offloading vessel (FPSO) where the oil and gas would be separated. The oil would then be pumped into a shuttle tanker while the gas would be exported via a 70 km (43 mile) extension of the West of Shetland Pipeline System.

How will such investments benefit the UK economy?

It will take about £1.9 billion in manufacturing and construction costs to bring Cambo into production. Half will be spent in the UK, creating over 1,000 direct jobs plus thousands more in the supply chain. The oil and gas from such projects would support the UK in several ways:

- The UK oil and gas sector generated £41 billion in taxes since 2010

- The sector pays 40% corporation tax on upstream profits – compared with 19% for other sectors

- It is predicted to contribute another £1.7 billion by 2026.

- The industry supported nearly 200,000 UK jobs in 2021.

- Many of those workers’ skills could be transferred into low-carbon energy industry.

How big is Cambo on a UK scale?

On a list of past and present UK fields Cambo is 80th in terms of oil and gas yield. For comparison:

- The Brent Field has produced three billion barrels of oil since 1975 making it 20 times bigger than Cambo.

- The Forties field has produced 2.6 billion barrels since the 1970s – and has 20 years more life.

- A recent report by Westwood looks at 16 potential developments on the UKCS for which government decisions are expected by 2023. These contain the equivalent of 730 million barrels of oil. Cambo represents around a quarter of this total.

How big is Cambo on a global scale?

An analysis by energy consultants Wood Mackenzie, of major projects progressing in 2021, found 19 which have been approved. These would collectively deliver 25 billion barrels of oil equivalent (boe) across Africa, the Middle East, Latin America, Russia, and the US.

The two largest, in Qatar and Russia, are 40-50 times bigger than Cambo. Qatar Petroleum is developing North Field East (NFE) – the world’s largest-ever liquified natural gas (LNG) project.

Of the others, 11 are 2-7 times bigger than Cambo. Cambo represents only 0.7% of new volumes being considered for approval in 2021.

What does this mean for consumers?

An analysis by OGUK, which represents the UK’s offshore oil and gas industry, shows that, while Cambo is important to the UK, it’s impact on global greenhouse gas emissions would be small. OGUK’s findings include:

- Global oil consumption is about 100 million barrels a day – so while Cambo is significant for the UK, it’s entire output could power the world for about 43 hours.

How much CO2 does oil and gas generate?

A barrel of oil generates 350-450 kg of CO2 if fully combusted so Cambo’s output of 170 million barrels would generate an average of 4 million tonnes of CO2 a year for the 20-year projected life of the field. This is about 1% of the UK’s current annual emissions. It’s important to note that these are not additional emissions. The UK’s total emissions are driven mainly by the overall amounts of oil and gas we use – not their sourcing.

The production and processing of oil and gas are also energy intensive with emissions equating to 17 million tonnes of CO2 in 2020. Under the North Sea Transition Deal, agreed with the UK government in 2021, the industry aims to halve these emissions by 2030 and reduce them to net zero by 2050. It also pledged to work on new technologies such as carbon capture and storage, plus hydrogen production, which could help decarbonise the wider consumption of oil and gas.

How clean would Cambo be?

Cambo will have the most modern equipment to reduce emissions and will operate with no routine flaring or venting of hydrocarbons so its direct CO2 and methane emissions will be less than half the average per barrel for UKCS installations when production commences. It would also be built electrification-ready, to be powered by renewable energy when feasible.

The potential impacts of Cambo on the sea and seabed have been subject of an exhaustive environmental assessment which has shown the risks to be minimal. This document is available at the website of the Offshore Petroleum Regulator for Environment and Decommissioning.

Would the oil and gas from such projects undermine the UK’s carbon budget?

The government’s Climate Change Committee has set out a ‘Balanced Pathway’ under which GHG emissions from economic activity in the UK would be reduced from just over 400 million tonnes of CO2e now to net zero by 2050. This plan allows for the continued but declining use of unabated oil and gas, including from developments like Cambo. So continued use of oil and gas is ‘priced-in’ to the UK’s carbon budgets and would not undermine them.

Shouldn’t we be cutting all emissions?

Yes. And we are! The UK’s national emissions have fallen from 950 million tonnes in 1990 to about 400 million tonnes in 2020. This was caused by cuts in demand – not supply. The biggest factors were the move away from coal to gas, growth in renewables, and reductions in fuel consumption by industry and households.

A key point here is that it’s demand that drives emission levels – not supply. Our population cannot change the way it uses energy overnight. So, if the UK stops extracting its own oil and gas, without an equivalent reduction in demand, then imports will have to rise with no reduction in overall emissions.

OGUK’s view is that the UK’s production of oil and gas should decline at roughly the same rate as demand – so giving the nation some energy security and keeping import bills down.

Share this article